NEWS

August 15, 2024

IN BRIEF

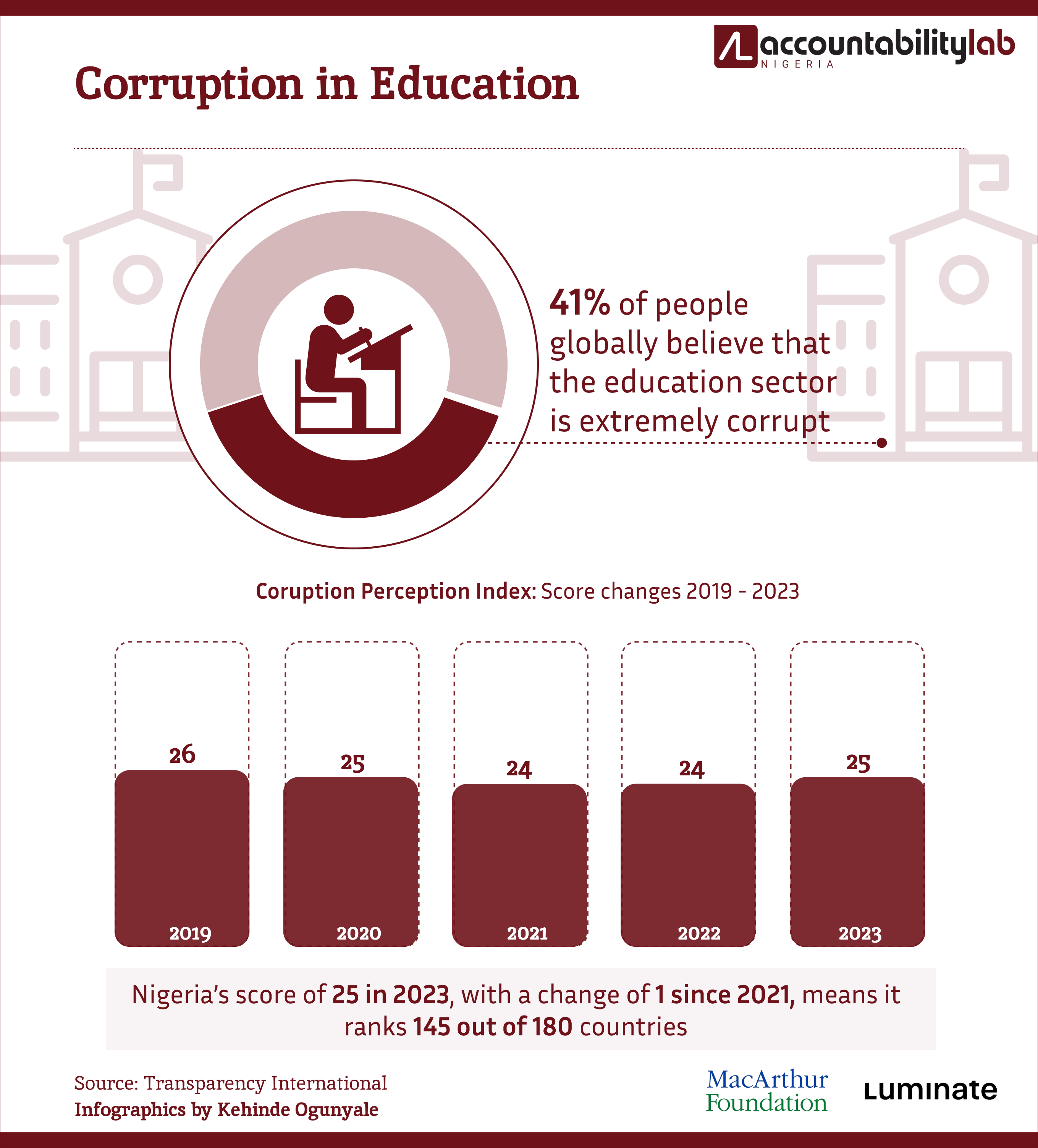

According to Transparency International, 41% of people globally believe that the education sector is extremely corrupt. It also adds that corruption is a major obstacle to achievingSDG4 (quality education) and to realising the universal right to education. Interestingly, analysts and scholars have suggested education as one of the ways to fight corruption, but what happens when corruption becomes part and parcel of the education sector? An article on Corruption and the Education Sector by Attahiru Jega highlights bribery and extortion [...]

SHARE

According to Transparency International, 41% of people globally believe that the education sector is extremely corrupt. It also adds that corruption is a major obstacle to achievingSDG4 (quality education) and to realising the universal right to education. Interestingly, analysts and scholars have suggested education as one of the ways to fight corruption, but what happens when corruption becomes part and parcel of the education sector?

An article on Corruption and the Education Sector by Attahiru Jega highlights bribery and extortion of money from students/parents for admission or grades, and/or for issuance of transcripts, as types of corrupt practices prevalent in the education sector. The Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (Jamb) registrar, Ishaq Oloyede, recently stated that between 2017 and 2020, over one million students were illegally admitted into various universities. In the same article,

This was, however, not the case with Mrs. Danjuma Kumbak, a lecturer at the General Studies Education Department at the Federal College of Education (FCE) Pankshin. Her decision to insist on students getting their true grades rather than padded results earned her a nomination for an Accountability Lab Nigeria Integrity Icon Award for a ‘person with integrity in the education sector’ in 2020.

Kumbak was faced with the choice of succumbing to or resisting bribe offers, but she chose the latter.

“As a level coordinator, I possess the authority to influence student grades, but I have never succumbed to such pressures, even when it involved a colleague’s child. My belief is that, as a civil servant, my actions should always be transparent and accountable. There was an instance where a student failed, and my colleague wanted me to pass the student, because my colleague knew the student, but I didn’t compromise my stand,” Kumbak stated.

Speaking with Kumbak’s colleague, Mrs Rufina Tuamyil, a Business Education lecturer who nominated her for the the Accountability Lab Integrity Icon award in 2020, revealed the moment she understood the depth of Kumbak’s incorruptibility.

“A student failed an exam and required it to graduate. Despite pleading from fellow colleagues on what seemed like a simple thing, Mrs Danjuma insisted on doing the right thing.”

Kumbak has been in service for 14 years and said she has dealt with pressure “to go with the flow,” but she maintains that her motivation comes from within—her conscience, which reminds her always to do what is right.

Doing right means refusing to follow the status quo and sometimes stepping on toes. This can bring resistance from those who feel aggrieved, looking for ways to get back at the ones who insist on doing the right thing. For Kumbak, her colleague testified that she is not a favourite with the other teachers, which could have an effect. For Kumbak, it was so bad that when she vied for the position of Treasurer in the University, most staff did not vote for her because they perceived her as unfriendly, according to Mrs Tuamyil.

She went on to say her decision not to be corrupt has attracted the disdain of some of her colleagues, who see her as someone who does not “have human feelings.” When asked why she nominated Kumbak, Mrs Tuamyil said that although Kumbak is not well-liked, she is known for integrity.

As a country, Nigeria ranks 145 out of 180 countries in the world on the 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index while scoring 25 out of 100, indicating a serious corruption issue that will not augur well for the country if strategies are not put in place. People who are doing the right thing are not given the pride of place to serve as a beacon to others. This necessitates promoting narratives and spotlighting people like Kumbak, who are steadfast in their profession.

According to a UNODC survey on corruption (2019), almost one in two bribes (45%) are paid to speed up or finalise an administrative procedure. In a large share of cases, bribes are paid for purely speeding up a procedure (38%), while the share of bribes paid to avoid the payment of a fine reached 21% in 2019. In the prevalence of bribery as a form of corruption, teachers and lecturers made the list with 10% in the 2019 survey, with customs/immigration officers, judges/magistrates, and police officers making the list.

The effects of corruption on Education abound, including its impact on administrators, students, and the community at large. Corruption reduces access to education, creates low-quality learning environments, and undermines our collective welfare, and if something is not done soon, the effects will be grave.

Unfortunately, the nomination for the Accountability Lab Nigeria Integrity Icon Award in 2020 is the closest Kumbak has come to being noticed for doing her job with diligence and accountability. Instead, she faces ostracization in the workplace, where people avoid her because they know she will not compromise. But she is not fazed, she said. “My motivation comes from within me through my conscience. As far as I know, it’s the right thing to do.”

Educators have a huge responsibility to uphold the right principles and ensure that the learning environment remains free from corruption and bias. Celebrating those who have chosen the straight path is one way to ensure the sanitization of the system.

This report is championed by Accountability Lab Nigeria and sponsored by The John D. and Catherine D. MacArthur Foundation and Luminate.