NEWS

June 29, 2024

IN BRIEF

“What!” Philip Ezegbulam unconsciously screamed when the news broke. The 59-year-old public servant couldn’t believe his ears. In his 22 years at the Police Service Commission (PSC) in Abuja, he had dismissed similar rumors in disbelief due to his faith in the Service. However, the truth he feared most was unfolding before his eyes. Established in 2001, the Police Service Commission recruits and maintains disciplinary control over Nigeria Police Force personnel. As the force upholds law and order in society, [...]

SHARE

“What!” Philip Ezegbulam unconsciously screamed when the news broke. The 59-year-old public servant couldn’t believe his ears. In his 22 years at the Police Service Commission (PSC) in Abuja, he had dismissed similar rumors in disbelief due to his faith in the Service. However, the truth he feared most was unfolding before his eyes.

Established in 2001, the Police Service Commission recruits and maintains disciplinary control over Nigeria Police Force personnel. As the force upholds law and order in society, the Commission must embody the highest standards of integrity.

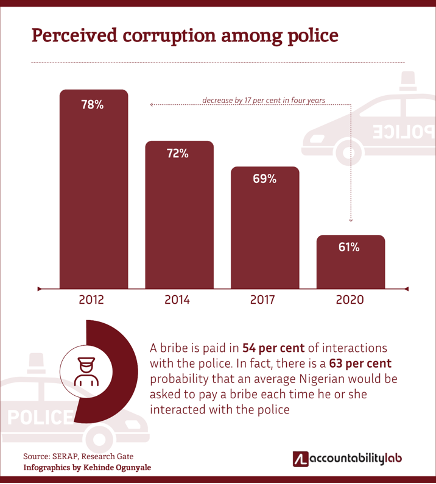

Despite this mandate, Ezegbulam became aware of troubling indications that integrity, a fundamental principle of the PSC, was eroding. In 2012, corruption within the Nigeria Police was reported to have peaked at 78 percent. During this time, Emmanuel Ibe, an official in the Commission’s recruitment unit, was implicated in unethical practices, particularly recruitment racketeering. Following investigations by the Nigeria Police Force and hearings by the Commission, Ibe was officially queried and subsequently suspended for his misconduct.

However, in November 2013, Ibe re-emerged, seemingly resilient. With a new Commission led by former Inspector General of Police Mike Okiro, who reportedly had close ties to the suspended official, Ibe was reinstated within six months. Okiro’s tenure at the PSC echoed the controversies of Ibe’s suspension, marked by allegations of recruitment scandals and financial impropriety.

Raising More Dust Through Unlawful Promotion

In addition to the arbitrary reinstatement of Ibe, Okiro disregarded the Commission’s seniority policy to elevate this indicted official within the leadership hierarchy. Despite 235 qualified PSC staff awaiting promotion under the previous commission, the arrival of a new chairman was expected to uphold due process. Instead, the chairman handpicked Ibe, a reinstated deputy director, and swiftly promoted him to Director of Finance and Administration on June 5, 2014.

This irregular promotion was retroactively dated to undermine procedural integrity further, superseding directors who had awaited promotion for two to three years. Unsurprisingly, the appointment sparked accusations of corruption.

Ezegbulam Challenges the Corrupt Status Quo

While many within the PSC recognized the blatant irregularities, most could only murmur in hushed tones, consoling themselves with the belief that in Nigeria, “everyone is doing it.” This mentality allowed the arbitrary reinstatement and corrupt promotion of unscrupulous officials to become a dangerous new normal, luring individuals into complicity with the corrupt status quo.

Breaking this cycle required a resurgence of moral courage, a willingness to challenge the norms, and championing a new standard of integrity. Philip Ezegbulam rose to the occasion. He stated, “I decided to draw the management’s attention, stating that his promotion was erroneous and that national promotion had been abolished in the public service since 2010. So, how was it that his promotion read 2011?”

Ezegbulam didn’t stop there. “I moved a step further, giving the Permanent Secretary a seven-day ultimatum to reverse the promotion, or I would write a petition against him and his new appointee, directing it to the Head of Service, Code of Conduct Bureau, and the Presidency,” he added.

Despite his efforts, the anticipated positive turnaround seemed distant. Would Ezegbulam now tire out, thus allowing these seemingly harmless corrupt practices to transform public service from societal pillars into hurdles to be circumvented?

Ezegbulam refused to be frustrated and did not give up. On June 25, 2014, he proceeded with the petition, signing his name to prove he could defend it.

In an attempt to break his resistance and persuade him to accept the corrupt status quo, Permanent Secretary Ossi George reached out to Ezegbulam, seeking an “understanding,” especially as all three—Ezegbulam, the Permanent Secretary, and Mr. Ibe—were from Southeast Nigeria. But Ezegbulam stood firm and refused.

Saagwe Brighten, who served as the director of appointment, promotion, and discipline at the Police Service Commission, was unsurprised that Ezegbulam rose to challenge the misconduct. “Ezegbulam is known as an upright man. What has always stood him out in service is that he hates injustice and will speak out no matter who is involved. Even those involved in this case were all Igbos, his brothers. But he never considered ethnicity,” he noted.

Corruption Fights Back

By refusing to cooperate with the top echelon of the Commission, Ezegbulam unwittingly declared war against himself. Fourteen days after submitting his petition, on July 9, 2014, Ezegbulam received a letter from the Commission informing him of his suspension pending the completion of the investigation against the official he had petitioned. However, just a month later, on August 14, 2014, Ezegbulam was dismissed without pay, citing “insubordination, lack of respect for constituted authorities, and declining productivity.” Despite his efforts to seek recourse under the Public Officers Protection Act and other public service regulations, his hopes for justice were dashed as his dismissal was upheld.

Paying the Price for Integrity

The battle against corruption took a heavy toll; Ezegbulam and his family bore the brunt of his commitment to a corruption-free system. “During this period, my wife, children, and I lived in deep denial. Daily meals were challenging, and paying my children’s school fees was difficult. I couldn’t afford my rent for three years, and my landlord had to verify our situation at my office. When he confirmed our plight, he even returned to support my family,” Ezegbulam recounted.

Beyond the financial strain and emotional trauma caused by injustice, Ezegbulam dedicated resources and time to seeking justice at the Industrial Court. Despite these challenges, he never wavered in his fight. “God and good friends were my pillars of support during this trial. Despite the hardships, I never regretted the trials I faced. I found solace in knowing that I fought for a just cause,” he affirmed. Mrs. Ezegbulam recalls her husband’s unwavering conviction, reflecting on the broader societal implications: “He often reminded us of the potential collapse in society if everyone chose silence or turned a blind eye to evil.”

Ezegbulam Sustains the Fight for a Just System Outside the Commission

As President Buhari’s administration took charge, signs of progress emerged in Ezegbulam’s long-standing battle. The presidency investigated Ibe’s questionable promotion to the director position. Consequently, Permanent Secretary Ossi George was found culpable and compulsorily retired in December 2015.

Even after leaving the Commission, Ezegbulam remained vigilant. He learned that Ibe had been appointed Acting Permanent Secretary by the Commission’s Chairman to replace George prematurely. Viewing this move as further corruption, Ezegbulam noted that no provision existed for an Acting Permanent Secretary, and Ibe wasn’t the most senior director then.

“I decided to address these concerns directly with the Chairman of the Commission,” Ezegbulam recalled. Undeterred by threats to his safety, he petitioned the Attorney General of the Federation, copying the Secretary to the Government of the Federation and the Head of Service, supported by evidence from the Public Service Regulation and Enabling Act Establishing the Police Service Commission.

Thanks to his established reputation, his efforts bore immediate fruit. The Head of Service received a directive to annul the appointment of the Acting Permanent Secretary. Subsequently, a permanent secretary was appointed from the core ministry to the Commission. The Chairman of the Police Service Commission faced scrutiny for attempting to exceed the President’s authority, the sole appointing authority for a permanent secretary as stipulated by law.

Ezegbulam Rewarded for Upholding Integrity

After enduring a four-year legal battle at the Industrial Court, Philip Ezegbulam finally obtained justice. The court ruled that his dismissal, which lasted four years and six months, was unlawful. Consequently, he was reinstated immediately with directives for promotion to the rank matching his peers in the service. Dated June 22, 2018, his reinstatement also included full payment of all outstanding entitlements and promotion arrears accrued during his dismissal period. Ezegbulam confirmed that the court’s order was diligently executed, resulting in three promotions within seven months.

Philip Ezegbulam’s unwavering integrity significantly fostered a culture of ethics within the Commission. Brighten said his commitment has empowered PSC staff to speak out whenever they observe wrongdoing. Ezegbulam’s case underscores that while opting for the easier path of corruption may lead to complacency and silence, individual courage can spark a transformative shift towards prioritizing ethics above all else.

Accountability Lab Nigeria’s Creative Storytelling Fellowship is proudly supported by the John D. & Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and Luminate.